AI-Assisted Reference and Photobashing for Pixel Artists

In November 2022 I published my AI and the Future of Pixel Art article both here and on Twitter and publicly documented my initial experiments integrating diffusion models into pixel art workflows. Since then, I've explored it much more thoroughly and have learned how to integrate the tool in ways that encourage me to be more ambitious with my work while relying less on photo and art reference.

For those who do not have hyperphantasia and cannot perfectly envision the finished product in their minds from the get-go, the usage of AI-assisted reference is no different from the use of traditional sources of reference, and the end result is as transformed from the materials as you make it, just as it is when using photo and art reference. As search engines have become more focused on selling you things than on being engines of search, they've grown increasingly useless for finding reference material. AI reference generation is a perfectly timed antidote to this, and, as a bonus, is even less directly derivative than traditional reference. Despite what you may have heard, there are no images stored in the models. The things you generate have never existed before! Image generation offers a potentially more ethical and less license-encumbered approach to reference material than the gathering of images of unknown origin from Google, Pinterest, etc. Like any other tool, it can be used for plagiarism, and if you choose to use it to do a plagiarism, that's on you.

Given the reality of this post-AI world, it is beyond reasonable for artists to learn how to use these tools, and outside of the Twitter Artist™ sphere most artists already have. It is imperative that all people have some level of AI literacy. Your personal and professional future depends on your understanding of how these tools work, how you can use them, and how they will be used against you.

It’s More Than Drawing With Squares

For relatively high resolution pixel art I always start with a non-pixel sketch/rough mockup, whether or not I use AI-assisted reference in the process; it is impossible to select the correct native resolution from the start if you don't know what the necessary details are in your intended style, and your resolution selection will end up dictating those elements of the piece rather than you consciously choosing them. Adjusting the resolution of a piece of pixel art or some portion of a piece is not at all trivial and requires total manual reworking of any rendering that may have been done previously. Utilizing elements of generations in mockups allows me to explore options I'm considering thoroughly and tailor my choices towards what will work best in pixel within any given constraints, guided by my artistic knowledge and experience. This allows me to spend more time executing my creative vision in the hand-pixeling phase and less time reworking and compensating for poor resolution selection.

Pixel art is not just scaled down drawings, and there is much more to it than consistently sized squares. While certainly not true of all pixel art, a fundamental aspect of "true" pixel art is that each pixel is placed with intent. Pixel cluster and pattern choices are a manifestation of the individual artist's creative expression. While I don’t currently use it, pixel generation does exist now, and is more viable than it was when I wrote my previous AI article. These tools do take some generally accepted pixel art "rules" into account, but the things that differentiate high quality pixel art still require manual placement. Every square makes a difference, and often serves multiple purposes at once. This fact is poorly communicated by most pixel art educational content—"First start with shapes, then add lines, then add anti-aliasing," and so on. This can be more digestible for beginners and makes for a more attractive infographic, but a more painterly approach, where consideration is given to the underlying meaning of the "color data" in each square in its greater context, is needed to deliver truly great pixel art. The thinking this requires is both complex and subjective, and since "true" pixel art is about having control down to the single-pixel level, human decision-making and self-expression are still very necessary in the creation of high quality pixel art, regardless of the involvement of AI in the process.

Pixel art is a multi-dimensional puzzle game where each choice affects all future choices. The order in which elements of the piece are "solved" is as much a part of it as the solutions themselves. Every time you place some squares, you should consider what the options are and how each one would alter the composition both within its small section of the piece and within the greater composition, as well as the balance and composition of color/perceived value, etc. You also should be thinking about how each choice will affect subsequent choices.

The solutions each pixel artist decides on are guided by certain self-imposed rules and standards. In my recent personal work I prioritize bold shapes with good rhythm and interplay, while avoiding specific cluster shapes I dislike. I prefer to utilize broken lines and line weight variance (intentional "jaggies") over anti-aliasing. I think it is not only possible, but likely, that advances in technology integrate these subjective "rules" in ways that make total manual placement obsolete, and at that point I and all other pixel artists will have to reevaluate how vital of a role carpal tunnel syndrome truly plays in our creative processes. Do you want to make cool stuff, or do you want to spend your precious time on Earth punishing your body in a redundant pursuit?

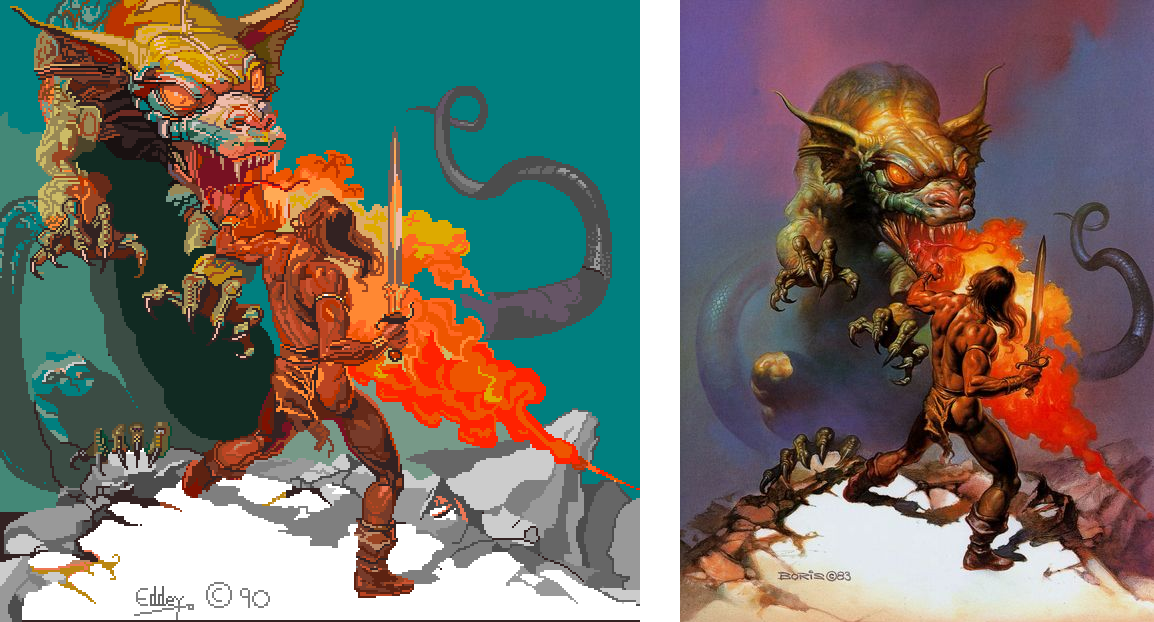

I've documented my current workflow in the creation of the above piece with the intent of inspiring other artists to experiment with these amazing new tools. I've never wished to extricate humanity from the act of creation, but time marches on, and each day brings more proof of inevitable change. This doesn't mean that people won't create anymore, but the ways in which they do it will change, as they always have. It’ll be cool as hell, relax! Pixel art is both my full-time job and my hobby, so I understand the fear and hopelessness most artists have felt since the introduction of this tech, but technology has been used to create art for as long as it has existed. Paint is technology. Computer monitors are technology. Now we've got something totally new—let's use it to make cool new stuff! The future of all art involves AI.

The attitude toward AI has improved considerably since my previous article. Its indisputable utility has percolated through the professional community to good effect, but there's still an undercurrent of hostility directed at those who openly use it.

AI is just a tool. Artists use tools to create things for people to enjoy. Not only is it impossible to force all artists to disclose their use, it's also irrelevant. Do people care what brand of brush was used to create a painting? Is a movie still good if it doesn't include "behind the scenes" footage? Sharing one’s artistic insights and processes is a gift, not an obligation.

If you want to learn more about image generation, read on, or click here if you'd prefer to skip directly to my process for this piece.

Tech

For this project I used the Automatic1111 UI on rundiffusion.com, a reasonably-priced pay-as-you-go service. Here is an option you can try out in your browser for free, and this is a more limited demo running the SD XL model. I'm not going to focus on the details of the software too much, as you can generate the same images through other means and with other interfaces. The tech is constantly evolving, so the conceptual fundamentals are more important than the specifics of the tool. Until we all have neuralink chips forcibly implanted in our brains at birth and all media is generated in real time to satisfy our specific individual desires (we are basically already there btw,) these arcane interfaces are necessary.

There are many ways in which these tools can be integrated into your process, and even more yet to be discovered. Get creative, don't be afraid to play around!

Practical Stable Diffusion Basics

Diffusion models manifest projections of a highly dimensional space onto a 2D plane. This space is more dimensional than the human mind can fully comprehend, but by adjusting prompt data (including but not limited to text input) you may discern something about the dimensions you are navigating through. This is very difficult to think about or describe, but you'll quickly develop an intuition for it. I find it useful to think of each part of a prompt as a "knob" or "slider." As you adjust the prompt slightly in one direction or another, you'll notice things about the dimension this self-created "slider" is navigating through.

There really are way more interconnected factors than one is able to get a handle on in prompting—a prompt in one model will not yield the same image in another. The dimensions through which you move using various types of prompt input will be different for each model, for each sampler, for each seed number, etc. You discover what these dimensions are and navigate through them by changing the input and discerning how the generated image has changed. I keep a log of each potentially interesting or useful generation and its data so I can browse through these and make note of what dimensions I'm moving through, and return to the particular point in the latent space in the future to make adjustments or as a jumping-off point for a different project. Yes this is crazy! Welcome to the future.

The text input is only one of many data points in a prompt, and it's never going to generate exactly what you expect. Different models have different strengths and weaknesses, and are affected by particular terms in different ways. Order does matter (more weight is given to words at the beginning,) as does spelling (yes, typos make a difference and can be used creatively) and punctuation, and the more words you have total the less weight each word has. You can adjust the weight by using parentheses () to increase the weight, and brackets [] to decrease. Adding more of either of these will increase the effect—so, more parens is more weight, more brackets is less weight. You can also use a colon followed by a number to get more precise weighting, although I haven't really found this necessary. Note that the exact formatting is actually specific to the Automatic1111 interface.

You can use negative prompt text to try to account for what you don't want, but "negative prompt: (((deformed hands)))" will almost never fix the hands. Think of negative prompt text as just another self-created slider through which you can navigate dimensions of the space. Your prompts don’t have to look anything like prompts you’ve seen from others. It’s all just sliders; do what works for you!

I don't worry about colors when prompting, since I'm very particular about the color relationships and values balance in my pixel art and will build the palette as needed while hand-pixeling.

It's rude to crib another artist's style—this is the case whether you're using AI or not. Certain LORAs aim to directly reproduce styles, and using these is as ethical as it would be for you to style match without AI. However, the usage of artist names in text prompts has a more ambiguous effect on the output than you may have been led to believe. In my experience, the output of most models is not strongly influenced by most names. Certain artists are more represented in datasets than others—you can use this site to see which are the most well-represented in the Stable Diffusion 1.4 dataset. Even if an artist is not represented at all, the additional text will affect the generated image in some indeterminate way, because all text has some effect. Each bit of text is a "slider."

You should have a good idea of the composition of the final piece before selecting the resolution, since certain aspect ratios will work better or worse for certain subject matter/poses. There are also more ideal places to crop a figure, such as at bust length, or slightly below the thigh. Your final piece does not have to be the same aspect ratio as your generated reference; you can generate ref in whatever size/ratio works best towards that end and compose your piece while using elements of generations however you want later. If you have a reference for the pose you want (whether self-drawn or drawn by someone else, or photo ref, or even generated ref,) you can slide this into the ControlNet module using the OpenPose settings. This is definitely not fool-proof, but it's worth trying, and you can create a guide pose manually if needed. You can adjust the settings of ControlNet modules to make them have more or less of an effect on the output, so lowering the weight on an OpenPose module will make the generation stick to the pose less strictly.

Note how even slight changes in resolution affect the generated image. Alterations to resolution DO NOT just stretch the image or make it larger or smaller. It’s a completely different slice of infinity.

CFG and Steps prompt inputs will typically default to figures in an acceptable range. CFG (aka "scale") is how closely the model will stick to your prompt. Steps is the number of denoising steps it applies. This is the "diffusion" in Stable Diffusion. You can try tweaking these slightly to iterate on a generation. A single digit shift in CFG will make more of a difference in output than a small shift in Steps due to the compression of the input range.

Seeds are the root of pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) and they serve to position you somewhere in the latent space. The same prompt with a different seed number will yield an entirely different image. Even slight changes to the seed number will land you somewhere else, so when you find a seed you like for the particular prompt you are working with, you may want to keep it while you tweak other elements of the prompt.

Use the recycle icon to reuse the seed number from your most recent generation, or the die to use a random one. You can even combine two seeds and adjust the weighting of each. I use this sometimes when I want to iterate slightly on a generation, by giving the second seed around 10-30% weighting.

Note that you can use the Refiner module to switch to a second model or checkpoint somewhere in the denoising process. I recommend selecting the model whose style is most similar to that of your desired output as your secondary refiner model.

There are too many sampling methods to really have a handle on all of them—keep in mind that the people who made these tools don't even fully understand how they work. Try out different samplers as you wish. Don't overthink it.

I haven't integrated inpainting, where only masked areas of a generation are filled with new image data, in my process, as my experience with it has been that it is not reliable enough to be worth the effort. Since I am doing so much work in the hand pixeling stage, I don't think it's necessary for what I'm using these generations for, but it's worth knowing that it's an option, and it’s fun to play with.

Process Overview

Going into this project (inspired by the song Fly to You by Caroline Polachek feat. Grimes and Dido,) I knew I wanted a tiny fairy and a to-scale dragonfly interacting, which almost certainly would prove challenging/impossible to generate with current technology. No nudity or at least none that would make it NSFW. The aspect ratio needed to be not too wide and not too tall, to optimize for display on X.

I played around with a few approaches, including sliding a sketch into img2img, and eventually ended up primarily in txt2img, with this generation as the kernel of the rest of the mockup.

As I'm generating, I'm saving generations and their prompts if they contain an element I like/feel will help guide me to my desired end result. If I like a right arm from this one, and a foreground leaf from that one, I keep both for later. No aspect of any of these images needs to be perfect; even the faint suggestion of an arm or whatnot is fine, whatever helps me to envision the piece. My brain will connect the dots.

Once I have a solid idea of where I'm going, I open the images I like in Clip Studio Paint and add them as layers in a single file. I use masking tools to combine elements of each, and then paint over things as needed—I'm also altering proportions (of the body or anything else) and perspective. I will often adjust values and colors of elements in this mockup file as well. Once I'm done with this, I'll see if I feel what I've got is sufficient to start pixeling, or if I want to throw this image into img2img to iterate on elements of it. The diffusion percentage controls how closely the new generation sticks to the image you put in. You can use Controlnet modules like Openpose on img2img generations too, just like you can on txt2img.

It doesn't really matter how sloppy this mockup image is, since I'm going to be reworking and perfecting things a ton in the hand pixeling stage. I usually begin with text2img, but It's also possible to begin your process with img2img. Doing this with a high diffusion percentage can be a good way to create a new image while retaining some essence of your input image, and to guide your generations in ways that the model you are using may not otherwise be inclined to do.

Once I have a composed ref image I'm feeling good about, I'll put that into PixelOver, a pixel art animation program of which I am using only a small fraction of its functions, and scale it down to the lowest possible resolution for the intended pixel style, referencing previous work of mine to gauge how small I can go. I use the palletizing and color adjustment tools to get the image to a workable place for me, considering how everything will translate to pixel. No need to worry about making the color count perfect for the end product; this image just needs to be good enough. I keep multiple resolution variants in case the one I initially select ends up being too big or too small. There's a minimum number of pixels necessary to render facial features, and sometimes this makes it so I must decide between pixeling the whole image at a larger resolution than I was planning and making the head larger relative to everything else. Often a larger head ends up being the better compromise.

I open the exported image at the scale I've selected as most ideal in CSP and get to work on pixeling, using my artistic intuition and knowledge of art fundamentals. A lot of it is about dividing and proportioning masses of color elegantly and then making that look like something (and, like I said, knowing what order to solve things in.) That's probably the next article. Layers came in very handy in making adjustments to separate elements of the piece and in handling transparency in the droplets and fairy wings. (Remember when people thought digital art wasn't "real art?" It wasn't long ago that the use of digital layers and brushes was derided, and Photoshop was vilified as a "magic art button." We've come a long way.)

While rendering, I reference non-generated images and use my body and things around the house as ref in combination with AI-assisted ref. The pixeling part of the process takes the vast majority of the time. This piece took over 30 hours just for hand-pixeling. All 94,488 pixels received my attention! If you'd like to learn more about this part of the creative process, read my well-researched, free articles on pixel art fundamentals that I've published previously on this site

Capitalism is a force, like gravity. Your opinion on it has no bearing on its inevitability. If you started the world over from the "big bang," human and techno-capital would always self-assemble into a world with AI image generation. What comes next is anyone's guess, but one thing is certain: during every historical paradigm shift people think "This is not like the previous times." In some ways they are right. New developments are unprecedented, but the patterns of how things play out repeat across time.

One's stance on AI art is more of a political statement than it is a logical response to reality. Just as there were many physicians who died believing that handwashing was bad post the introduction of the concept by Ignaz Semmelweis in 1847, anti-AI doomers are the anti-handwashers of our era. If you are a working artist, you either already are using AI, unintentionally or not, or will soon be. It will never disappear, but the market for artists who don't use AI, like the market for doctors who don't wash their hands, is only going to get smaller. Submit or be subsumed.

While AI is not something I ever wished for, it's here now—the cat's out of the bag, but you've got to admit it's a pretty cool cat. Resistance is futile! You're going to use these tools, AND you're going to have them used against you. The only way out is through. Regulations are only as effective as they are enforceable, and, as I’ve discussed in the past, attempts to regulate will result in these tools being available only to corrupt entities, further disempowering the individual. This endangers everyone, not just artists. While regulations will certainly come eventually, they won't result from the benevolence of those in power, but rather their desire to be the only ones allowed to generate images of seriously ill princesses. There will always be other nations who regulate differently or not at all, and they will use the tools to uplift themselves and achieve their own ends, guided by their own subjective understandings of ethics.

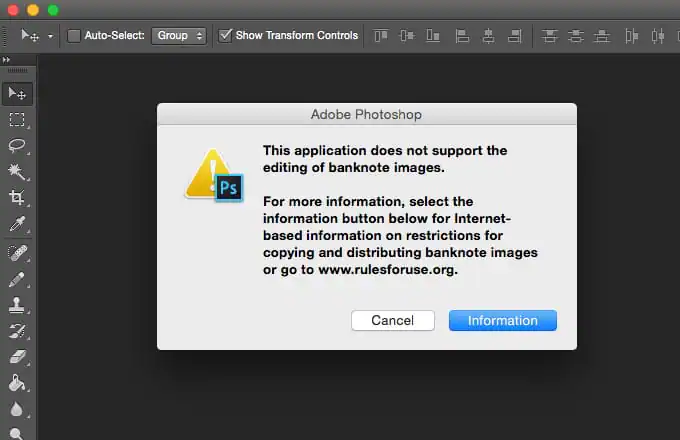

As to the critique about the use of copyrighted materials in the development of these models: any argument against AI on copyright grounds would have chilling effects at an incomprehensible scale. If Nintendo had their way you would be billed every time you even thought about Princess Peach. Photoshop certainly would not let you draw her, at all (in the same way it won't let you edit a dollar bill.)

Copyright is not meant to protect you, and it does not. Big corporations and media conglomerates are the only ones with enough money and power to enforce it; even so, compliance is limited by global disconnection in law and culture (see: the unlicensed IP mashup maximalism which is the dominant aesthetic of carnival attractions everywhere.)

Many art movements and subcultures, including pixel art and sample-based music like hip-hop and EDM, were built on the sharing and reuse of media enabled by the unenforceability of copyright. Suddenly appealing to the threat of authoritarian copyright enforcement as a means to hamstring an artistic revolution is regressive, not progressive.

My experience with using AI in processes for making pixel art so far is that it has empowered me to think bigger and produce higher quality works. The things I've learned in making these works are applicable elsewhere, regardless of process. I rest easy knowing my work has inspired other creatives and entertained countless pixel fans the world over. Isn't that what it's all about? Hold my hand, as we step into the future together.

Subscribe to Pixel Parmesan

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox